Let me pump your intuition

A bat, a p-zombie, and swampman walk into a Chinese room.

Hello everybody,

This week we’re looking at thought experiments with David Edmonds.

You can find the companion article here: The “repugnant conclusion” that an Oxford philosopher couldn’t escape

I love “Would you rather…?” games.

In fact, if you and I ever sat around the table for more than 10 minutes, I suspect I’d be throwing hypotheticals your way. How serious or silly those hypotheticals are will depend on the time of night and the drink in our hands.

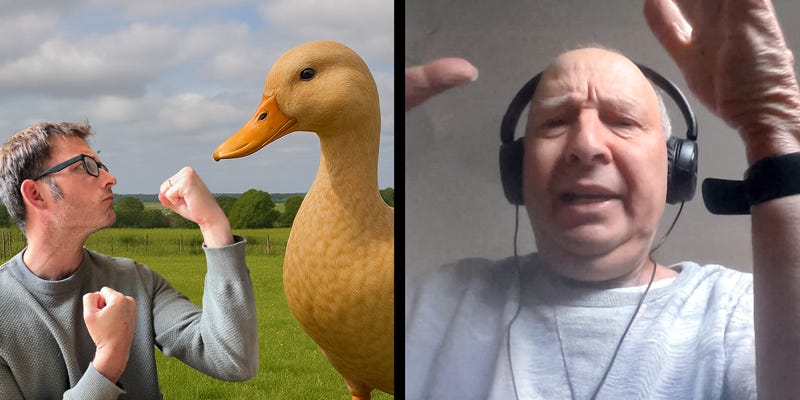

Would you rather fight a horse-sized duck or 100 duck-sized horses?

Would you rather be too hot or too cold?

Would you rather spend eternity in hell with your loved ones or eternity in heaven without them?

Silly questions, fun questions, important questions.

At the heart of a good “Would you rather…?” is what philosophers call an “intuition pump.” They invite you to reflect on certain principles and background assumptions — how dangerous a duck can be, the nature of temperature-based suffering, and the willing sacrifice of true, pure love.

If we step back from the pub or dining table and reframe this a bit, we call these “thought experiments.” On my social media pages, thought experiments are consistently the highest performers. They’re fun, science-fiction hypotheticals that invite either a philosophical response or a “This would never happen!” from a lot of people.

This week, we ask: What makes a good thought experiment, and are they actually more philosophically serious than a “Would you rather…?” game over beers?

P.S. Please comment or write in with your answers to those three questions above.

Tinkering with our intuitions

The “experiment” in a thought experiment is all about controlling the variables. A good thought experiment will often involve various scenarios on the same theme, with some variables changing across the scenarios. For example, let’s take one of the most famous thought experiments in philosophy: the trolley problem.

The basic setup is that you’re in charge of a runaway train. On the track ahead are five people who cannot move out of the way for whatever reason. The train will hit and kill them. But you can pull a lever to redirect the train onto another track, on which lies one equally immobile person. Is it better to “let” five die or to “choose” to kill the one?

That’s the basic setup. But now we can tinker with the experiment to test all sorts of intuitions. Let’s say it’s two vs. one. Do the numbers change anything? Let’s say it’s one young doctor vs. three already-dying elderly people. Does “life impact” make a difference? Let’s say the one is your daughter, sister, or mother, and the five are convicted murderers. Does your relationship affect the ethics of the situation?

In each case, we are testing individual hypotheses about our ethical intuitions. As Edmonds put it, “Thought experiments are like a laboratory in the mind. Most problems in the world are very messy, and a thought experiment lets you control everything except one factor. And, because the only way you can just tweak one difference is to make it bizarre, then they often become outlandish.”

This is why our runaway train victims cannot move. This is why Mary is locked in a black-and-white room. This is why we need Swampman, zombies, and “vampire problems” to do the work. Of course, this is also why great science fiction is so great. When you imagine future worlds, different but not too different, you often present artistic and extended thought experiments. The worlds of Isaac Asimov are often used in philosophical discussions. The Matrix, Westworld, The Truman Show, Severance, and Groundhog Day feature regularly in syllabuses across the world.

But philosophers would be neglecting their job if they didn't ask the question: Are thought experiments actually worth it? Do they do anything useful, or are they only a bit of fun? Edmonds thinks so. As he put it:

“The person who has invented the thought experiment has a very strong intuition about how he or she responds to it and assumes, normally correctly, that everybody else will respond to the thought experiment in exactly the same way. And although they're not an argument, because they're presenting a picture, they do point you in a direction of an argument or a viewpoint.”

A philosopher will often—implicitly or not—lay out their argument in premises leading to conclusions. Often these premises are not empirically proven or even provable, but they are presented as either obviously true or they are presented in a way that invites you to agree with them. Thought experiments are ways in which we can win over that agreement.

For example:

Premise: Language understanding is more than the correct use of syntax.

(See John Searle’s Chinese Room thought experiment)

Premise: We can never know what someone’s inner mental life is like.

(See Thomas Nagel’s What Is It Like To Be A Bat thought experiment)

Of course, there are problems with this. Edmonds believes that most people will usually agree with a philosopher’s intuitions, but not always—especially if you consider different philosophical traditions, different centuries, and different cultural starting points. It might be “obvious” that we should save five rather than just one, but in a Kantian tradition, that’s not obvious at all.

So, what do you think about thought experiments? Do you think they’re useful or just a bit of fun?

IN YOUR OPINION

For those interested, here is the full list of answers to this week’s poll:

Severance – 11 mentions

The Truman Show – 10 mentions

The Matrix – 7 mentions

Arrival – 6 mentions

Black Mirror – 5 mentions

Minority Report – 4 mentions

True Detective – 4 mentions

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – 4 mentions

The Leftovers – 4 mentions

Lost – 4 mentions

Fight Club – 3 mentions

Attack on Titan – 3 mentions

After Life – 3 mentions

Inception – 3 mentions

I have not seen all of these, but I have seen most, and I can certainly attest to how great they are. But from this list, one stands out for me as especially powerful: Arrival. I first saw Arrival months after it came out and was blown away by the entire plot—not to mention the brilliant way it’s shot. And so, I went away to find and read the original Ted Chiang story it was based on: Story of Your Life.

I recommend it with all my being. Of all the stories I’ve read in the past 10 years, none has devastated and reoriented me more than that one.

Next week, we’re exploring Socrates and the Socratic method with Agnes Callard. And so, I’m asking:

What’s been the most important conversation of your life?

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

MINI READING LIST

Interview with Agnes Callard with the Guardian who are okay, I guess. No Mini Philosophy, though.

The hidden power of unanswerable questions - Big Think

RESOURCES

This newsletter contains my reflection on the topic at hand. Here is a list of the material shared in this email, as well as extra content about the topic that I've shared on my other social platforms:

The companion article inspired by my conversation with David Edmonds

My short video about thought experiments, featured on Big Think’s Instagram page

The full, unedited audio interview with David Edmonds:

Jonny is the creator of the Mini Philosophy social network. He’s an internationally bestselling author of three books and the resident philosopher at Big Think. He's known all over the world for making philosophy accessible, relatable, and fun.

More Big Think content:

Big Think | Big Think Business | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Books

"When you imagine future worlds, different but not too different, you often present artistic and extended thought experiments."

When I was a sophomore in college I had the most dynamic and interesting professor for a class on the ‘60’s. I was so enthralled with the experience that I met with him to discuss my desire to get my doctorate in history. He allowed me to express my idea and then throughly shot me down. He went on to explain how he could tell that I would not be the type of person who could become obsessed with one tiny idea so much that it would cause me to travel anywhere in the world to read any sort of thing on it, in any dusty musty basement of a library or historical archive, not be able to sleep until I had discovered everything there was to discover about it and that ultimately no one else would give a crap about but me. As he said these words, I tried desperately and unsuccessfully to hold back tears. I was gutted. I went in to that meeting so confidently knowing what I wanted to do with my life and now I had nothing. That conversation was over 30 years ago and it has lived rent free in my head since because he was absolutely right. I had never had someone be so brutally honest with me and as much as I wanted to hate him for his candor, I had to accept the reality of his words. Now, I will confess that it took me awhile, many 10 years, to understand that he did me a great service that day. He forced me to truly think about myself and my abilities for the first time. I have shared this story with many of my students over the years to make them ‘hear’ the ugly truth that they may be avoiding. I’m forever glad to that professor because that conversation led to the path that brought me thirst to teaching and then to administration.