Three theories of truth and a load of BS

My chat with the CosmicSkeptic, Alex O’Connor

Hello everybody,

This week we’re looking at truth and religion with

.You can find the companion article here: Does the evolution of reason undermine the belief in evolution?

My two young boys are in the bath, and they’re screaming at each other.

It’s fairly common these days, however much I might hope otherwise. In fact, I’d even argue it’s become part of the bedtime routine: bath, fighting, crying, friends-again, giggling, books, sleep. All kids like structure.

“You’re lying!”

“No, I’m not!”

“Yes, you are!”

“No, I’m not!”

On and on it goes in an unverifiable loop until someone steps in to distract or remove one of our combatants.

My kids are obsessed with “truth” at the moment. Being called a liar is the worst insult you can fling, and being told you got something wrong is a shame no one wants to bear. Of course, a five-year-old doesn’t know what “truth” is. A three-year-old doesn’t know what “lying” is. But they both know that the words are important. They know the label “liar” is a reputational albatross. They know that being “true” or “right” matters (at least in this household).

Truth, for the Thomson boys, is not about reality, facts, or grand philosophical metaphysics. It’s about winning a fight with your brother in the bath. This week, we explore how surprisingly modern this idea is.

Deflating your truth

Given how important “truth” is to many people — today and throughout history — you’ll be unsurprised to know that philosophy has a whole deck of theories about it. As the old joke goes, if you put two philosophers in a room to answer “What is truth?” you’ll get seven different answers.

The correspondence theory of truth argues that something is true if it “corresponds” to some real state of affairs “out there.” The coherence theory of truth argues something is true if it agrees or “coheres” with the other things I already believe. The pragmatic theory of truth argues something is true if it has “cash value” — it works with the world and helps us get by.

All of which are lovely, but never quite hit the mark. The correspondence theory depends on assuming both that there is a real world and that we can ever actually know anything about it. The coherence theory allows for any number of internally coherent nonsense theories — without ever having to leave the room. The pragmatic theory seems to render “truth” unrecognizable compared to how most people understand it.

According to philosopher Alex O’Connor in this week’s interview, that might be just the problem. O’Connor is a “deflationist” when it comes to truth, which means that he thinks the terms “true” and “false” have nothing to do with “truth” at all. In fact, the notion of “truth” is so slippery and evasive as to have no semantic or metaphysical content whatsoever. Instead, saying “this thing is true” has non-truth-related implications. We’re actually just saying, “this thing is important,” “this thing was said to me once,” or “this thing is better than not-this-thing.”

This is how O’Connor put it:

“I prefer a deflationary theory of truth, which says that to say something is true is just to assert it. So, if I say, 'Two plus two is four,' and you say, 'Is that true?' well, that doesn't really add anything. You've already said it. The idea that 'truth' adds something to the proposition doesn't make sense. So, when you ask, 'Is two plus two true?' you're already just restating it. There's no added depth, no metaphysical essence. It's just an expression.”

There are, of course, real-life implications to the deflationary theory of truth. Major philosophical beliefs almost always have practical knock-ons. If you don’t believe in free will, how does that affect the justice system? If you think goodness is entirely relative, can murder ever be “right”? And, in this case, if truth adds nothing to a statement, are we on a slippery slope to a world of what the philosopher Harry Frankfurt called “bullsh*t” — where people just say whatever they want without caring at all for the reputational weight of “truth”? Bullsh*tters are worse than liars because they have absolutely no concern for the truth whatsoever. Truth is a tool. It’s a weapon. It’s only a word, and it’s one of many.

If “truth” adds nothing, then does it become nothing? And what does a world without truth actually look like?

IN YOUR OPINION

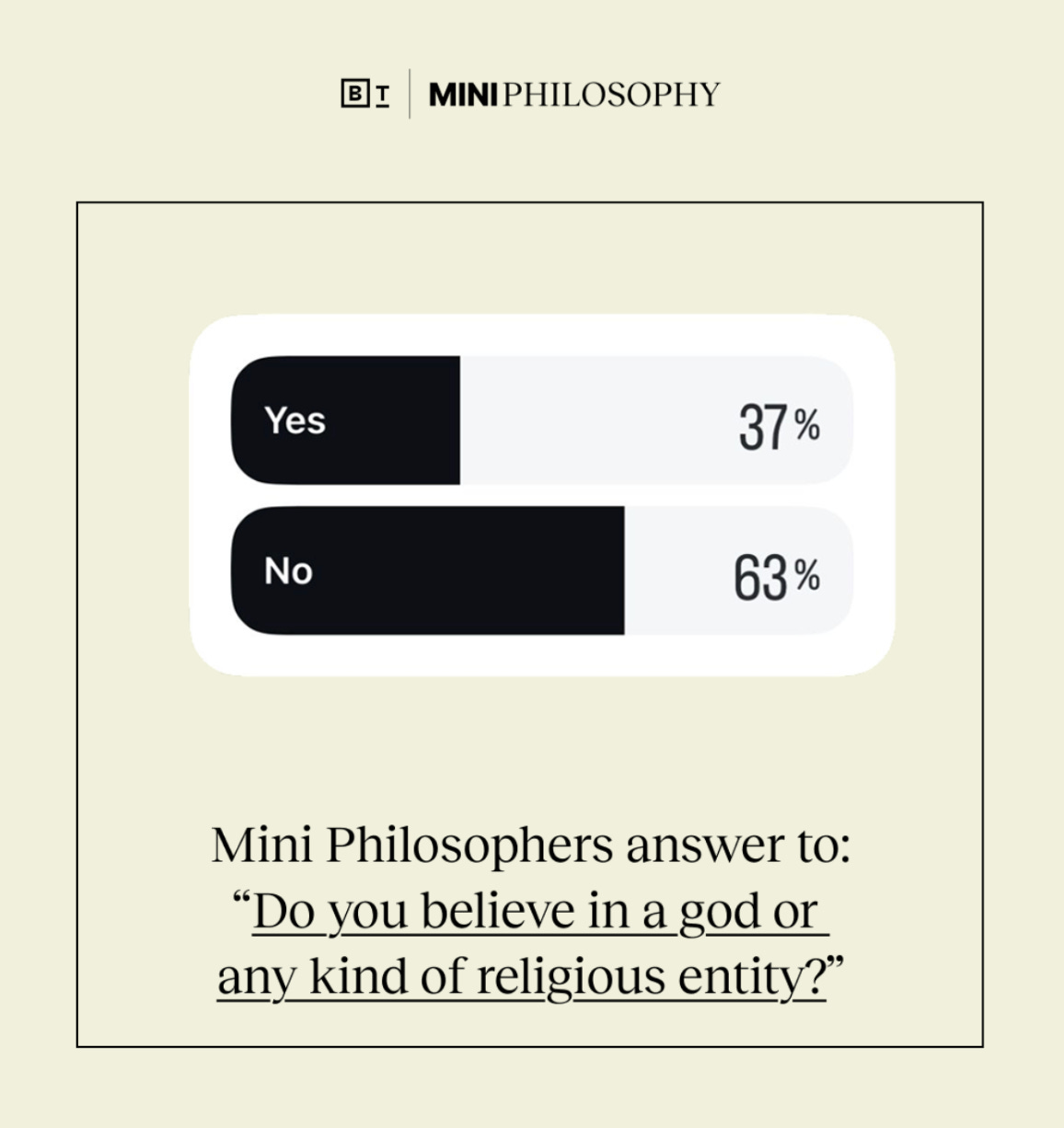

Lots of replies this week to the humdinger that is “Do you believe in a divine force?” In fact, three people decided to send me their multi-page journal reflections from decades of meditating on the matter. Sadly, I didn’t have the time to read many of these, but I did take away the gists.

Of all the answers I received this week, it was nice to be reminded of this little story from Michael Tscheu in the Substack comments:

“A story I like:

Within a conservative sect of Judaism, when reading the Torah, they do not speak the word “Yahweh.”

Just speaking the word would make God too small.

I really connect with that.”

I connect with it, too, Michael. When I was younger, I loved to talk about God, belief, and religion. I could spend hours debating and unpacking theological nuances and philosophical differences.

These days, I find myself fumbling around. I’m increasingly sympathetic to the feeling (not knowing) that there is some spiritual “other” to the Universe, but the second I’m pressed or pushed on the matter, I find the concepts drift away. It’s like grasping some mental mist or trying to keep quantum particles still. Observing them — let alone articulating them — seems to utterly disappear them.

For some, that will mean that I don’t actually believe anything. That these religious concepts are empty. But all I can say is that it doesn’t feel empty.

Next week, we’re exploring “the end of history” with famous historian Dan Snow. And so, I’m asking:

Would it be good if people could vote on every major issue?

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

MINI READING LIST

RESOURCES

This newsletter contains my reflection on the topic at hand. Here is a list of the material shared in this email, as well as extra content about the topic that I've shared on my other social platforms:

The companion article inspired by my conversation with Alex O’Connor

My short video explaining Plantinga’s Divine Reason, featured on Mini Philosophy's Instagram page

The full, unedited audio interview with Alex O’Connor

Jonny is the creator of the Mini Philosophy social network. He’s an internationally bestselling author of three books and the resident philosopher at Big Think. He's known all over the world for making philosophy accessible, relatable, and fun.

More Big Think content:

Big Think | Big Think Business | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Books

Disclaimer: I'm way out of my depth here, but that's never stopped me from wading deeper.

2 + 2 = 4 is true as a consequence of the defined properties of natural numbers. It is real by definition. It is somewhat real in the sense that it has implications when you file your taxes etc.

However, the number 2 is an idea abstracted from experience. Abstraction leaves out part of the real experience, 2 is a detached fragment of something like 2 rabbits. The truth of 2 + 2 = 4 depends on real issues such as what is being counted and how long you expect the statement to apply. 2 rabbits + 2 rabbits could equal dinner for a pack of wolves or 40 rabbits or some rich fertilizer and a pile of bones. The problem with truth is that it's never quite true because everything connects through a dense web of cause and effect, whereas our idea of a thing ignores the irrelevant connections to make a discrete thing thinkable. Whatever I am thinking, my idea may be relatively true but never quite true. I am reminded of another Big Think, that the only exact map of a thing is the thing itself.

People often invoke something like “2 + 2 = 4” to assert that truth must be absolute and self-evident. It's simple, clean, and seemingly immune to interpretation. But this inclination reveals more about our need for certainty than it does about how truth actually works in the material world.

Yes, 2 + 2 = 4 is true within the framework of arithmetic, which is a symbolic system built on defined rules. It’s internally consistent. But the real world isn’t a closed system like math. The brain doesn’t process the world in such neat, isolated equations. We experience life through limited perception, language, emotion, and messy context.

So while 2 + 2 = 4 represents a kind of idealized truth, it's a poor metaphor for the kind of truth we try to describe in social, emotional, political, or physical reality. Truth in the real world is entangled in bandwidth limits, linguistic abstraction, and flawed sensory interpretation.

It’s not that truth doesn’t exist. It’s that the way we access and describe it is constrained, like a toddler trying to explain gravity without words.