The hopes and dreams of a yellow dwarf

Do you like your science mainstream or fringe? Well, I’ve got both.

Hello everybody,

This week we’re poking at the boundaries of science with Rupert Sheldrake.

You can find the companion article here: Fringe or frontier: Is our current scientific paradigm still the best fit?

Robert Hooke did not invent the microscope.

The first iteration of what would become today’s microscope came in 1590. The Dutchmen, Hans and Zaccharias Janssen, put a series of magnifying lenses together in a tube and—hey presto—microcosmia was revealed. The decades between the Janssens and Hooke were spent tinkering, improving, and refining the microscope until, in 1665, Robert Hooke devised the best one to date.

Hooke did not invent the microscope, but he did show the world what it could do. In 1667, Hooke wrote one of the most important books in the world, and few people will know its name: The Micrographia. The book was a philosophical and scientific explainer about the microorganisms and invisible things that make up our world. But, most importantly, it was a beautiful, ornate, visual expression of those things. With delicate, exhausting care, Hooke sketched out a flea, a louse, the pores of a cork. He revealed to the general public, for the first time, those invisible things only previously seen by scientists: things like spores of mould and cells.

I often think about the average Joe or Jane who first saw those pictures. Before Micrographia, they might have heard vague notions of the "invisible world,” where people spoke of mites, vapours, or spirits that moved through the air. But this would have seemed abstract, folkloric, even theological. Suddenly, they could see it. Suddenly, the world around them would have felt far, far busier. It’s one thing to accept that there might be mysteries too small for the eye, but it’s another thing to see, in ink and on paper, the monstrous detail of a flea’s leg or the ordered pores of a leaf. The invisible became visible, and that changes everything.

Hooke’s Micrographia was part of a paradigm shift that made up the scientific revolution. It was another brick in the wall that would eventually create the building known as “mechanistic materialism.”

It’s a wall that this week’s interviewee thinks we ought to break down.

The hopes and dreams of a star

This week, I spoke with the maverick and always-entertaining philosopher, Rupert Sheldrake. Sheldrake has built a reputation over the years for his idea of “morphic resonance” — the idea that “self-organizing systems,” such as biological animals, can inherit memory from other such systems. A bird can pass memories onto other birds; a tree can pass memories onto humans.

It would stretch the “philosophy” in Mini Philosophy too far to devote much time to unpacking and dissecting the arguments or proposed evidence for morphic resonance, but all we need to know is that Sheldrake believes there is more to the world than what fits within our current scientific paradigm. He thinks that there are things that “normal science” calls “pseudoscience,” and there are things scientists tend to ignore or ridicule because they are inconvenient data points. Sheldrake is not talking about angels, leprechauns, chi, or Yogic levitation — although those might have a different role to play in his alternative model for the world.

The biggest problem, according to Sheldrake — and far easier to digest than “morphic resonance” — is the presence of consciousness. Because, under our current paradigm of “mechanistic materialism,” we are told to assume everything in the world is simply a larger compound of smaller parts: atoms make molecules, molecules make cells, cells make organs, and organs make organisms. We’re also told that none of these smaller component parts is conscious or purposeful. So, within our current understanding, we have consciousness — mine and yours — emerging from a Universe utterly without consciousness. Which seems difficult to square.

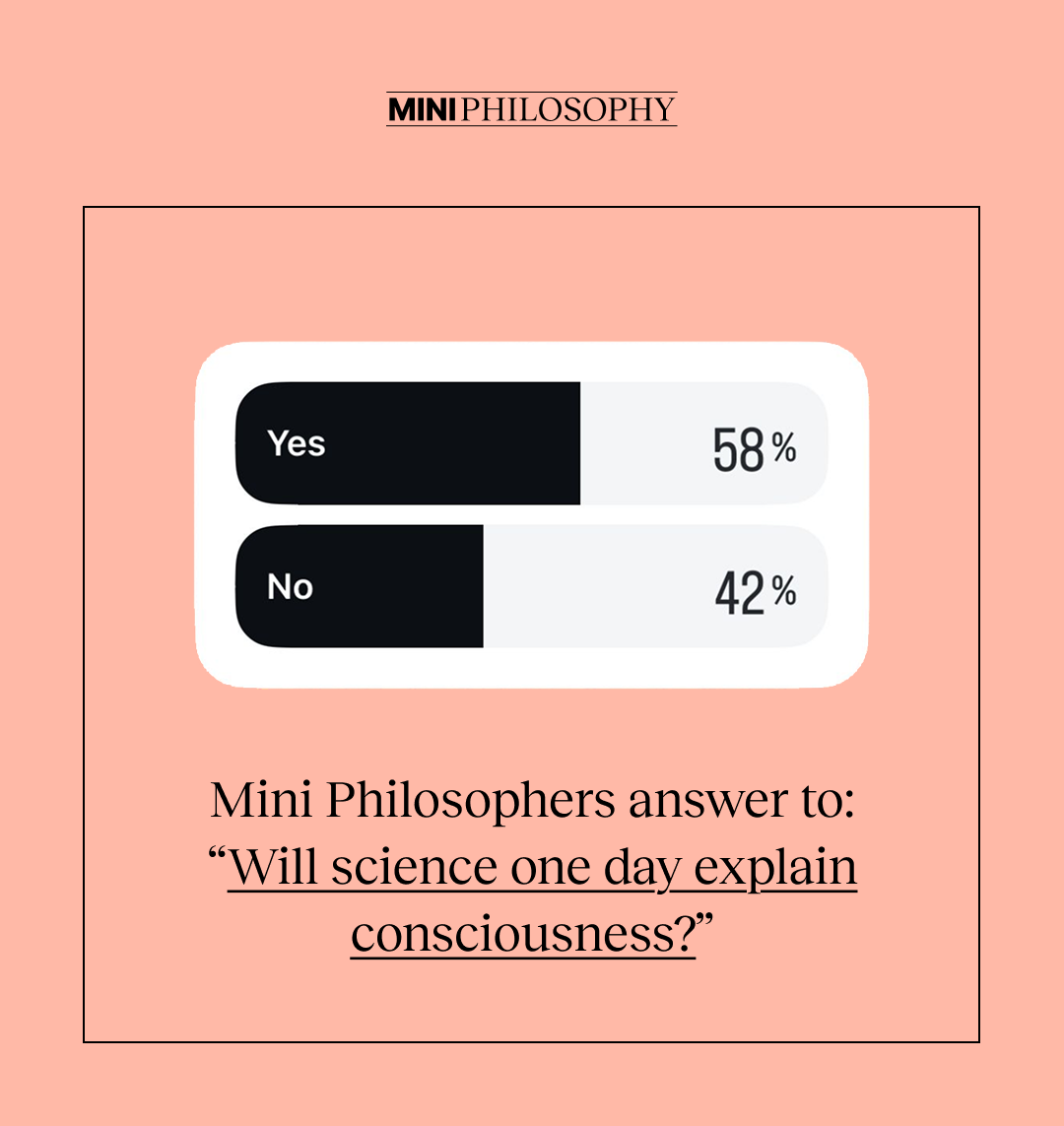

What, then, are our options? Either we dismiss consciousness as an illusion or an epiphenomenal, pointless accident, or we kick the can down the road. We say, “Yes, it’s a mystery. But it won’t be forever. The scientists of tomorrow will reveal the answers we lack.”

Sheldrake, though, thinks we will never find those answers in our current scientific paradigm. Consciousness is not just a “hard problem” — it’s an “impossible problem.” How can you get consciousness from unconscious substance? How can you get a mind from mindless matter? Thoughts from atoms? Instead, Sheldrake argues that if we are to solve this problem and treat consciousness with the seriousness it deserves — and I, for one, certainly think my consciousness is important — we need another model.

For this, Sheldrake suggests something closer to panpsychism, where “consciousness may be part of matter — even an electron or an atom may have a tiny little bit of consciousness… which means when you get something as complex as the brain, a more complex consciousness can emerge from simpler consciousness.”

Let’s entertain the idea. Let’s rewire our assumptions and obliterate our paradigm. Imagine a world where panpsychism is true. What then? What changes? This is a vision Sheldrake imagines:

“The sun is a vastly complex system of electromagnetic activity, more complex than our brains, with constant rhythmic activity — 11-year cycles, solar flares, sunspots. It's so teeming with activity. And the more we learn about the sun, the more active it seems. And if the electromagnetic activity of our brains is the interface between mind and body, as most people more or less assume, then the electromagnetic activity of the sun could be the basis of the solar mind.

If we saw the Sun as conscious, and that would then raise the question, what about the other stars? And if we saw the whole galaxy as conscious, with the stars as like cells in the body of the galaxy or in the brain of the galaxy? And then finally, the whole Universe is conscious. What difference would that make to cosmology and physics? Because if stars and galaxies have intentions and purposes and other things that go with consciousness, it could lead to a very, very different cosmology. A very, very different kind of physics.

If the galaxy is conscious, one could at least try to think: What kinds of things could a galactic mind do? One thing it could do is shape the structure of the galaxy and its activity.”

Of course, this idea lies somewhere between science fiction and New-Age fantasy. I can already hear my colleague Ethan Siegel at Starts With a Bang tapping his caps lock and typing out a Slack message to me.

The point is not that we think this is the way things are, but rather that, according to Sheldrake at least, there are other ways of viewing the same set of facts in the Universe from a different starting point. Thought experiments like these are not necessarily true, but rather, they are intended to jolt us out of our assumptions. And the unexplainable and intractable awkwardness of consciousness does seem to imply we need to jolt our assumptions in one way or another.

IN YOUR OPINION

Lots of interesting thoughts this week about the limits of science. I had a lot about consciousness, which I think we’ve explored enough, but I feel this answer both represents many others and introduces an interesting idea. It’s from Holly in the comments of last week’s post on Substack:

I don’t think science will ever be able to explain God. No matter how much we discover, God, as I understand it, is an immaterial thing undiscoverable by any empirical investigation. Aquinas’ statement that we must take a leap of faith is as true now as it was then — science will always stop before we have to leap.

Many people wrote in to say God, gods, or the spiritual will never be able to be explained, but Holly adds an extra “why.” What does “science” actually mean? When the term started to be commonly used in the 14th century, it meant something like “knowledge.” Science was everything you could know. And, given that many theologians from the 14th century onward thought you could know at least elements of the divine, religion was often considered within the remit of science—or “natural philosophy,” as it was called.

Interestingly, the deeper root of scientia — the Proto-Indo-European skei — meant “to cut” or “to split.” Knowing, in this sense, was about distinguishing one thing from another—carving the world into joints. Seen in this light, modern science still cuts: It focuses on what we can empirically observe and test. But perhaps that leaves other ways of knowing available to us — intuition, revelation, reflection. Science, powerful as it is, might still be just one marble in the whole bag we call “knowledge.”

So, what do you think: Is science all our knowledge, or just a “cut” or “portion” of knowledge?

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

Next Week:

Next week, we’re exploring changing the world with Rutger Bregman, and I’m asking:

What charity work, if any, do you do regularly?

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

MINI READING LIST

Effective altruism is stumbling. Can “moral ambition” replace it?

What is effective altruism? Philosopher Peter Singer explains.

RESOURCES

This newsletter contains my reflection on the topic at hand. Here is a list of the material shared in this email, as well as extra content about the topic that I've shared on my other social platforms:

The companion article inspired by my conversation with Rupert Sheldrake

My short video about our existing paradigm, featured on Big Think’s Instagram page

The full, unedited audio interview with Rupert Sheldrake:

Jonny is the creator of the Mini Philosophy social network. He’s an internationally bestselling author of three books and the resident philosopher at Big Think. He's known all over the world for making philosophy accessible, relatable, and fun.

More Big Think content:

Big Think | Big Think Business | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Books

I would argue that the great disconnect between faith and science is not the fault of science but the scientists.

As the author states,

"He thinks that there are things that “normal science” calls “pseudoscience,” and there are things scientists tend to ignore or ridicule because they are inconvenient data points."

It is the very narrow and rigid straight jacket of modern scientific presuppositions, i.e. mechanistic materialism--which in their ignorance and narrowness they would not call baseless presuppositions, but proven scientific facts, and in saying so destroy the meaning of the word "science"-- that forces a disconnect with religion. As if all that could possibly exist is what we can in some way observe! As if the current state of our knowledge is complete! Yet in their misplaced self-confidence the broader scientific community would discredit and ridicule adherents of religion, or at best require they jettison or modify certain tenets to accommodate their so-called "science".

Nevertheless, wisdom is justified by her children. The thinking religious person has no problem with science, but with bias. Our problem is not with data, but data skewed by inherent bias.

Why is there something instead of nothing? Where have we ever observed something arising spontaneously from nothing?

Why is there order instead of disorder? Where have we ever observed order arising spontaneously from disorder?

What other conclusion can we draw other than that there is an eternal (and genius) conscious mind in back of it all? We do not need to be able to observe or measure such a mind in order to see the clear evidence for it everywhere. Any competing conclusion reeks of bias--show me where my reasoning is flawed.

Can our esteemed scientists even see the contradiction between their presuppositions and their observations? I always relish the scientist who is willing to admit his/her ignorance, for truly the growth of our humility must correlate with the pace of scientific discovery.

I can hear them shouting me down even as I type. Long live the truly liberated mind.

When a message is hidden by a cipher and you succeed in breaking the cipher, you know both the hidden message and the cipher. You do this all on your own.

Knowledge does not come about purely because of observation.

Why are ciphers breakable?

Because hidden messages have structures. And ciphers themselves have structures.

Simple ciphers are easy to break because easy to invent. To break a cipher, we have to invent it first.

Since there is no end to how complex a cipher can be, our knowledge is for ever limited to what is humanly breakable. That is to say, however much we know, it is always very little.