Hello everybody,

This week we’re looking at the philosophy of altered consciousness.

You can find the companion article here: How the brain creates heaven: The philosophy of psychedelics with Susan Blackmore

In 1965, John Riley, the “Demon Dentist,” spiked John Lennon’s drink.

Riley, a friend of The Beatles, had just finished hosting dinner for Lennon and George Harrison. They were all reclining in postprandial contentment when Riley announced that the sugar cubes they had all put in their tea were laced with LSD.

“How dare you f----king do this!” Lennon screamed, and he and Harrison stormed out of the house.

Of course, it was too late. The acid was already working its way into their bloodstreams, and the hallucinations were not far behind.

Harrison had the better of it. As he put it later: “I had such an overwhelming feeling of well-being, that there was a God, and I could see him in every blade of grass.” Lennon, though, was trapped in a nightmare. He thought everything was on fire and became “hot and hysterical.” Eventually, his psychedelic inferno guttered away, and Lennon finished the night in Harrison’s house, which suddenly resembled a huge and welcoming submarine.

Anyone who’s listened to The Beatles’ 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band will be unsurprised to learn they were fans of hallucinogenic drugs. In fact, most of the creative classes were in the 60s and 70s. Aldous Huxley wrote an entire book about his psychedelic journey. Salvador Dalí regularly experimented with opium and famously said, “I don’t do drugs. I am drugs.” Jean-Paul Sartre had a bad trip, which meant he would see giant crabs follow him through the streets of Paris for weeks.

There is a long, ancient tradition of drug use among the artistic sort. But why? Why are these hallucinogenic and sometimes out-of-body experiences so important to so many people — from famous musicians to that bloke you knew at school?

To answer that question and much more, I spoke with the famous philosopher and cognitive scientist Susan Blackmore.

Here’s the philosophy of tripping.

There’s not only one kind of consciousness.

As you read this now, you are possessed of a “normal” consciousness. It’s normal only in the sense that it’s the most common, and it’s the one scientists and philosophers have historically been most concerned about. This is the sapiens in Homo sapiens. It’s that curious mixture of attention, intention, and imagination swirled with occasional sparks of rationality, mathematics, and logic. When Descartes famously wrote, “I think, therefore I am,” he was largely referring to this kind of consciousness.

But your mind is not a one-trick pony. It easily wanders into other kinds of consciousness. As William James put it, “Our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.”

You do not have to take spiked sugar cubes to appreciate this. If you have ever been suddenly and rudely interrupted in that just-before-sleep state of mind, you’ll understand what different consciousness means. There is a kind of near-sleep that floats around in the liminal. One foot in the sensory world, one foot in the imaginarium of dreams.

Some drugs will give you a sense of altered consciousness, and Susan Blackmore has long taken these drugs. She is fascinated by those experiences that can offer a radically different perspective on the world. For Blackmore, it’s a source of inspiration. It’s what often steers her scientific and philosophical work. It gives new dimensions to her friendships.

Drugs are still a social taboo in many communities around the world, and there’s an unquestionable risk to some of them that it would be irresponsible of me to ignore. But there are other ways to experiment with altered consciousness that are just as ancient as smoking certain leaves. This is what Blackmore says about it:

“I do a lot of meditation. I've just, a couple of weeks ago, come back from a 10-day online retreat, which was about practicing the Jhanas. The Jhanas are a series of eight increasingly deep meditational states that you get to through concentration. They're really fascinating. And I've had one or two of them spontaneously in other situations. So, I'm really fascinated by the neuroscience of what's going on in our brains that does this. The actual Jhana teacher thinks that the first Jhana, which kind of invokes this energy—and there's all these spooky stories about subtle energies and chakras and stuff like that—but he reckons it's a self-induced dopamine rush, which then decays into neuroadrenaline and produces the next stage. I just love the idea that there can be neuroscientific explanations for these things.”

William James used to take nitrous oxide in a similarly experimental and philosophically curious way. It was an easy way to stimulate altered states of mind. But James argued that there are many different types of consciousness and many different ways to access them.

It’s a scientifically inaccurate trope to say, “Your brain only works at 10% of its full potential.” Evolution is not so clumsily ineffective as to give us such an energy-sapping organ like the brain for it to only work at 10%. But it is true to say that the consciousness you occupy right now is only one of a great many. Your brain can do many more things than you might think. Your mind can go on journeys and reveal things that your waking, rational mind can never touch.

IN YOUR OPINION

Last week, I asked you about intoxicated revelations — what have you realized about being drunk, or if you’ve ever taken drugs? This answer came from the comments section, and I love it:

“While being drunk or high, I realise that I do need my prefrontal cortex, especially the dorsolateral bit, which is the utilitarian, logical decider of deciders (Sapolsky, 2017), to function as a female adult with responsibilities. However, during the time I put dlPFC to rest for the evening, I found that I am actually pretty good, as a person — useless when drunk, but not mean.” – Kaerin Hagley

In vino veritas — in wine, there is truth. It’s curious that a vast variety of cultures, from every point in history, seem to have a version of this idea. The Bulgarians say, “The truth is in the bottle;” the Chinese say, “After wine, blurts truthful speech;” and the ancient Babylonians used to say, “When wine enters, secrets come out.”

As with any common and enduring aphorism, there’s usually a glimmer of truth to be found. And Kaerin points out why. Intoxicants dampen that part of our brain that is responsible for making logical, rational decisions. It means you might be “useless,” but that you still have something to say. There is something in your heart that you usually keep locked away. But with booze or drugs, you think, “Why not?”

The ancient Persians put this to use. They said that if you needed to decide anything major, you should make two decisions. First, in the rational clarity of day. Second, in the swirling haze of the drunk. Apollo and Dionysus together, around a table. A good decision was one where your sober self and drunken self agreed.

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

Next Week:

Next week, we’re exploring suffering with David Bather Woods and so I’m asking:

In what ways is life hard for you right now?

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

MINI READING LIST

Podcast with Bather Woods about Schopenhauer and compassion.

Stephen Johnson, editor extraordinaire, talks about suffering over at Big Think.

RESOURCES

This newsletter contains my reflection on the topic at hand. Here is a list of the material shared in this email, as well as extra content about the topic that I've shared on my other social platforms:

The companion article inspired by my conversation with Blackmore

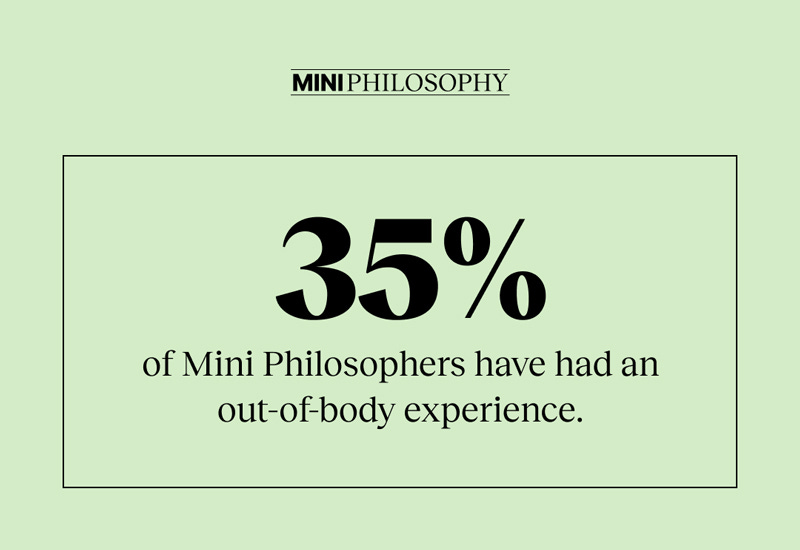

An interview clip exploring out-of-body experiences with Blackmore, featured on Big Think’s Instagram page

My short video exploring out-of-body experiences, featured on Mini Philosophy’s Instagram page

The full, unedited audio interview with Blackmore:

Jonny is the creator of the Mini Philosophy social network. He’s an internationally bestselling author of three books and the resident philosopher at Big Think. He's known all over the world for making philosophy accessible, relatable, and fun.

More Big Think content:

Big Think | Big Think Business | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Books

Thinking about the drunk truth thing and I am a bit confused not to say flabbergasted cause my therapist told me there is such a thing as mean drunks and my hubby swears he doesn’t remember or mean anything he said. He doesn’t remember

What to believe, ? He was kinda breaking up with me 🥹 but he says he doesn’t remember anything

Astral projection and telepathy are both possible and, once experienced, never forgotten...