What Tolstoy, Shakespeare, and a Japanese monk teach us about happiness

The beauty you find in 2,500-year-old cliche.

Hello everybody,

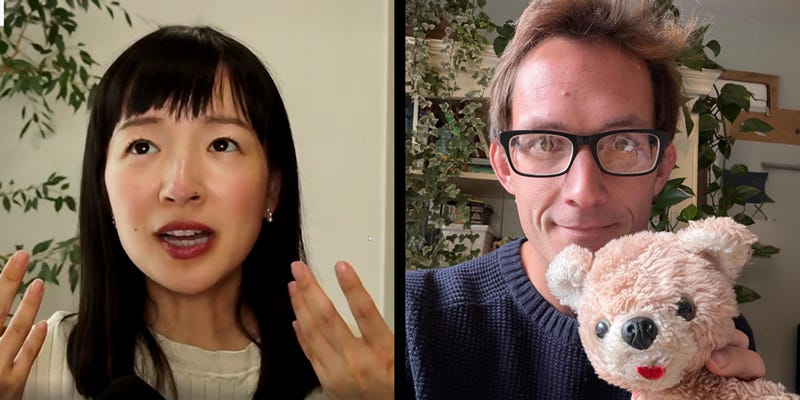

This week we’re looking at sparks of joy with the legendary Marie Kondo.

You can find the companion article here: 6 Japanese concepts you need to know, according to Marie Kondo

Mark is at a bus stop.

He’s sitting on the wobbly, not-quite-flat seat you get in bus stops, and he’s grumbling about the rain. It’s a heavy, October rain that splashes the ground, dirties your trousers, and makes a mockery of a bus stop shelter. Mark is miserable.

The person next to him answers his phone. The rain is too loud to hear much of the conversation, but Mark’s irritated about it nonetheless. It’s been an irritable kind of day, the kind to strike from the calendar and move on. Best not to talk about it, really.

Suddenly, the man lets out a huge, thunderous laugh. The people in the bus stop on the other side of the road can hear it. It’s a laugh that makes it through the rain, the sound of passing lorries, and Mark’s seething self-pity.

The man carries on laughing. He laughs and laughs and laughs until he sounds like he’s going to die. His eyes are watering, he’s bent over, and he’s laughing.

And Mark finds himself smiling. He looks at the man, and he smiles a bit more. The longer the laugh goes on, the wider the smile becomes. Eventually, Mark is laughing along. He doesn’t know the joke, he doesn’t know the man, but it’s impossible not to join in.

This week, we look at “sparks of joy,” and how a spark becomes a fire, and how a fire can warm even the dreariest bus stop mope.

The truth and beauty of a cliché

Everything changes.

That’s one of those trite, overused phrases that I’m sure you’ve read a hundred times. If you’ve subscribed to this newsletter, I suspect you’ve read your fair share of philosophical essays that remind us life is impermanent, everything dies, and we only ever have the present moment.

2,500 years ago, Heraclitus said everything is flux. 400 years ago, Shakespeare wrote, “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player, That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, And then is heard no more.” And 100 years ago, Virginia Woolf was cruel enough to add, “The very stone one kicks with one’s boot will outlast Shakespeare.”

But the true masters of “everything fades” are the Buddhists, and especially Japanese Buddhists. Japanese Buddhism places the inevitable cycle of existence right at the heart of its philosophy, and as a culture, Japan is far more attuned to the seasonality of life. In fact, the Japanese have 72 words for various microseasons across the year.

“What’s your favorite season?” you ask, kicking piles of crispy, autumnal leaves.

“Well,” your Japanese friend says, taking a big breath.

So, everything changes. We’ve been telling ourselves that for as long as recorded philosophy shows. The question then becomes: How do you respond to that? You’ve heard it, but what do you make of it? Well, I would suggest there are three reactions you can take to the impermanence of existence.

The first is to ignore it. A few weeks ago, we looked at the brain of a philosopher and why some people might or might not like big, existential questions. It might be that some people simply aren’t wired to entertain impermanence. “That’s lovely, dear,” Heraclitus’ mum says, “Now bring in the washing.”

Of course, the other reason someone might ignore impermanence is that life is simply too all-consuming. Life is too hard, too busy, too much to really sit down and reflect on the universal structure of entropy. Some people barely have the energy to count to 72, let alone think up 72 seasons.

The second reaction is a kind of existential despair or ennui. In his Confession, Tolstoy lays out the darkness of this kind of despair beautifully. For Tolstoy, the longer he focused on the inevitability of death — “everything dies” — the more life lost its sweetness. As he put it:

“I had as it were lived, lived, and walked, walked, till I had come to a precipice and saw clearly that there was nothing ahead of me but destruction. It was impossible to stop, impossible to go back, and impossible to close my eyes or avoid seeing that there was nothing ahead but suffering and real death—complete annihilation.”

If there’s a better and more lyrical description of despair than Tolstoy’s, I’d love you to tell me.

Finally, there is the solution we come to this week. And this is when we say, “Yes, everything changes, and everything dies, so let’s consciously, deliberately, wholeheartedly enjoy what we have while we have it.” Savor the moment. Carpe diem. Cherish.

The Japanese Zen master, Eihei Dōgen, described everything we know, including what we love and cherish, as little more than “Moonlight, reflected in dewdrops… shaken from a crane’s bill.” It’s an intentionally poetic description. Dōgen doesn’t say, “Life will end.” He doesn’t, as Tolstoy does, say, “a blood vessel in the heart will burst anyway.” He describes transiency with — and as — beauty.

In this week’s Mini Philosophy interview, I spoke with Marie Kondo about the “sparks of joy” you find around the house. Kondo argues that we ought to mindfully touch and cherish the things in our house. As we pick up a jumper, a cup, a pillow, a pot, an empty bottle, or a used tissue, our body will respond. Sometimes, it will lift up — “almost as if each little cell in your body is rising” — and at other times, sink down.

Kondo and Dōgen’s philosophy does not deny transience or succumb to existential despair, but finds joy, beauty, and even meaning in the present moment. Each of these sparks of joy might be a fleeting spark in the pan. They are gone in a moment. The collective brilliance of a lifetime of sparks will fade to blackness eventually. We all do. But Kondo’s advice is that we can relive and recreate these sparks over and over again. It takes constant effort. It requires us to be grateful, attentive, and present all of the time. But in this way, happiness is a fire we constantly stoke.

As Thich Nhat Hanh put it:

“Impermanence means that everything is changing, including the happiness that you are experiencing. Happiness lasts only for one step and if the next step does not have mindfulness, then happiness will die. But, you are capable of making a second step which also generates happiness.

Happiness is impermanent; but we can continue to generate the next moment of happiness.”

IN YOUR OPINION

A heartwarming, uplifting assembly of joy this week. Here are some of my favorite answers. It turns out that reading other people’s sparks of joy is, itself, a spark of joy.

YouTube videos of the theme music from the cartoons I watched when I was a kid.

Thinking about my breakfast that I’m going to have the next morning, before I fall asleep.

Hearing my favorite song in public.

Watching the slow rhythms of test cricket.

Watching people hug in public.

Sunlight on my body, specifically on my face.

My cats purr when I pet them.

Witnessing the exact moments the street lights turn on. Like the switch was flipped for me!

When someone still remembers my name after meeting me once a while ago.

Walking through a city as it’s waking up.

Seeing flowers that have turned towards the sun.

Seagulls.

Next week, we’re exploring existential risk with the bestselling author of Precipice, Toby Ord, and so I’m asking:

What do you think is the likeliest cause of human extinction?

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

MINI READING LIST

RESOURCES

This newsletter contains my reflection on the topic at hand. Here is a list of the material shared in this email, as well as extra content about the topic that I've shared on my other social platforms:

The companion article inspired by my conversation with Marie Kondo.

My short video exploring the idea of the 8 million gods, featured on Mini Philosophy's Instagram page

Jonny is the creator of the Mini Philosophy social network. He’s an internationally bestselling author of three books and the resident philosopher at Big Think. He's known all over the world for making philosophy accessible, relatable, and fun.

More Big Think content:

Big Think | Big Think Business | Starts With A Bang | Big Think Books

I'm 60 years old and sparked to go and get my childhood teddy bear out of the box he's been in for too many decades. I know he will still be sending out joy.

I threw away my relationship with my son. It did not spark joy🌟. All that lack of communication while he spends all his time napping. Entitled 2yr old. I'm better off