Into the brave and reckless hearts of explorers

Nothing great was achieved while sitting on the fence.

Hello everybody,

This week we’re looking at the philosophy of history and invention.

You can find the companion article here: Why the people who actually drive history aren’t in the textbooks

A man is leaving his family

His wife and three children come to say goodbye. His wife hugs him for a minute and kisses his scratchy, grizzled beard. His kids cling to their daddy’s legs and cry. No one knows what kind of goodbye this will be.

Yurik detaches himself and walks away. He does not trust himself to look back as he jumps onto the ship. The longboat is busy with provisions and stinking with crew. There is hardly any room to move around, and the only empty spaces are the seats they need to row. Three months before, Yurik petitioned the Jarl to explore the western seas. “There will be gold,” Yurik said. “There will be good soil, gentle weather, and woods filled with deer.” Of course, Yurik had no idea. He didn’t even know if there would be anything in the western seas. But he knew that he needed to try.

The history of exploration is steered by tales of bravery, resourcefulness, and ambition. In the hearts of all explorers, there is a desperate curiosity, a need to discover, that others will often label reckless or pathological. What compels Yurik to leave his family, risking death, on the basis of an educated guess? Glory, probably. Money, often. But at the heart of all discovery is a set of virtues or psychological dispositions that “regular” people don’t possess.

Today, all the seas have been charted and all the lands of Earth have been discovered, but there is still exploring to be done. There is a forever-fog at the fringes of what we know. There are great unmapped territories for innovation, technology, and science to reveal. We need explorers today as much as at any time in human history.

The journey of a life

In this week’s Mini Philosophy interview, I spoke with the popular historian Anton Howes, and we rambled our way around the history of innovation, economics, and the Tudors. But Howes also mentioned a curious thing. It was about how people used to see invention. This is how he put it:

“In the 17th century, the primacy of trade and the primacy of exploration are seen in the same way as invention. When Francis Bacon writes about Christopher Columbus and his discovery of the New World and the invention of gunpowder or the printing press, big inventions, he uses the same words, right? So, to explore in this sense is effectively to invent a new trade route or to invent a new route. So, the way that they think about discovery and invention is conceptually much more similar than it is today, where we kind of separate out industrial inventions as being a kind of category of their own.”

I am not a historian, and so I cannot help but see the philosophical in what Howes is saying. Reframing science and invention in this “discovery” way is interesting in that it presupposes two things: first, a kind of epistemological realism and, second, an irrepressible confidence.

By epistemological realism, I mean the idea that there are answers out there to be discovered. There is an extreme kind of philosophical skepticism – dating back to the ancient Greek Pyrrho – that there is no such thing as “truth” or the answer. We have only interpretations. We have best fits and best guesses. And today, when we talk about Popperian falsification or Bayesian interpretations, we’re kind of conceding this point: Science is never “right,” just “less wrong than it was.” But when inventors and scientists of the 17th and 18th centuries were talking about discovery, they thought there were answers out there. They believed that if they enquired deeply enough or worked hard enough, they would reveal the truth like a frontiersman discovering a new mountain.

This epistemological realism is what fuels confidence. If you wholeheartedly believe there is a solution to be found, then you will carry on going until you find it. If you never doubt that there is some land out there to discover, you will carry on sailing. This self-assured confidence is what often fuels the greatest discoveries and inventions. How many times did the Wright brothers hear they were fools to think they could fly? How long were the nights that Frances Arnold thought her experiments on enzymes were as doomed as critics said? How many times did Gutenberg fail before he gave the world the printing press? Modern science might not have much truck with “truth” and “solutions,” but the motivational thrust of believing in solutions is what propels so many of history’s greatest thinkers.

The image of discovery is a powerful one. It’s what motivated Yurik the Viking, Enlightenment scientists, and yesterday’s inventors. But it’s also an existential one. Viewing your life as a journey is old philosophical wisdom. Your life is a voyage, and the future will be full of golden lands and droughty sands. There’s both shipwreck and glory up ahead. But the lesson here is to view the future as a destination you can control. We all have ships to sail. Whether that comes to ruin or glory, who can tell? But we all need to have a destination in mind — an idea of who we want to be.

And while the winds will certainly buffet us off course, and “here be monsters” may not always be a euphemism, I hope that you arrive safely where you want to end up.

Do you agree?

IN YOUR OPINION

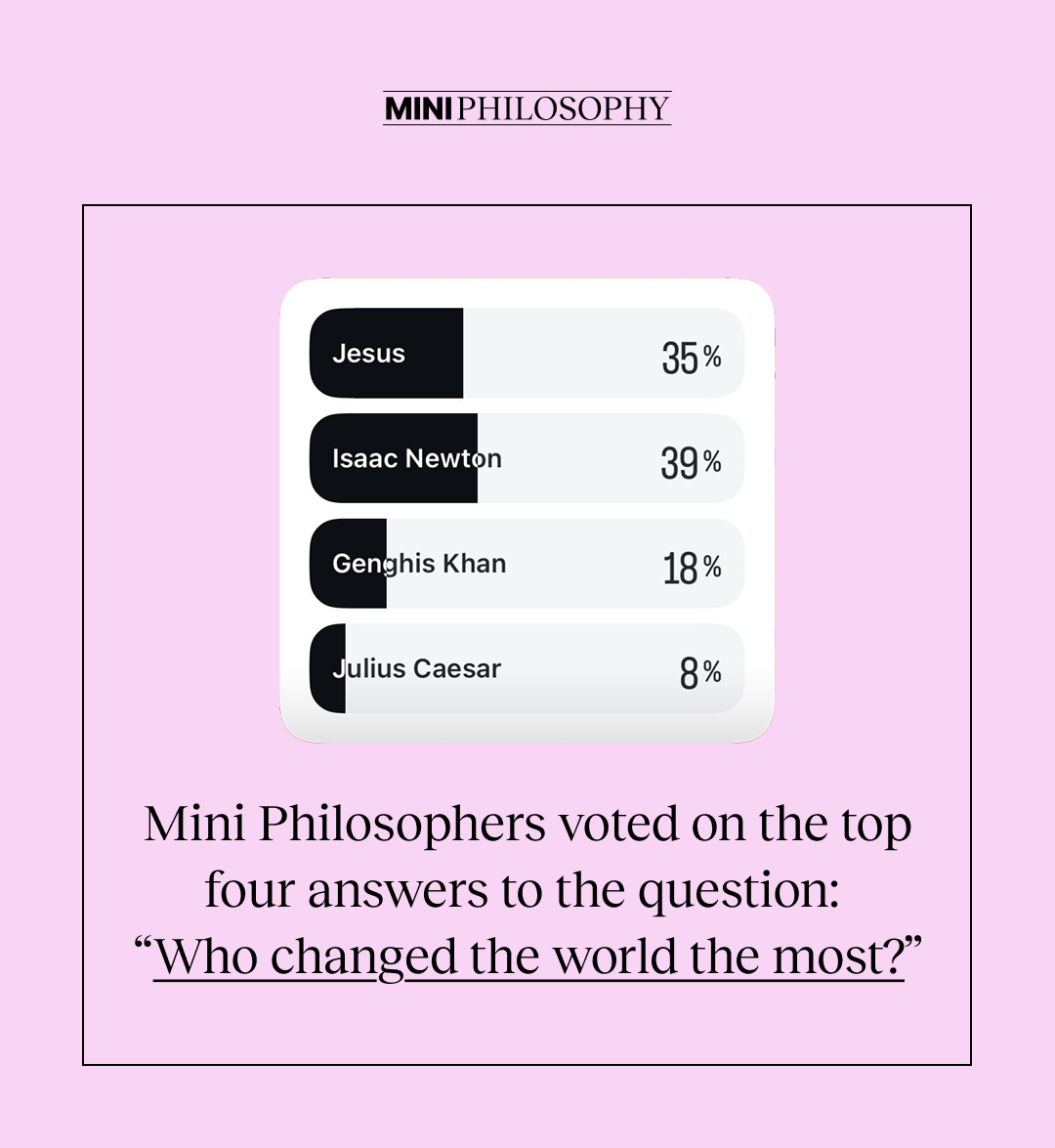

An interesting question this week, and the poll results were a curious mixture of religious sages, scientists, and political leaders. But one of the fullest answers came via email this week from Tim. It read:

“I’d say Fritz Haber — an interesting one because his ‘invention’ was very much double-edged. He invented the Haber process for making ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen gas — vital for fertiliser but also high explosives.

He’s probably responsible for the population boom in the 20th century and the reason there can be so many humans on the planet today, as we simply would not be able to grow enough food to support so many!

But also he’s known as the father of chemical warfare so…”

A great answer, and I think there are two things to draw out from this. First, how “greatness” is complicated. Anyone above the age of ten years old will probably have worked out that the world is not made up of saints and sinners. Life is not a comic book, and there are few unblemished, faultless heroes in history. Haber is a good illustration — he was a scientist and family man who loved his country. In times of peace, this gave us the Haber-Bosch process, which now helps feed about 50% of the world. Roughly 4 billion people are alive today because of Haber. On the other hand, he invented chlorine gas and other chemical weapons, which mutilated and killed thousands in the most horrendous way — because he loved his country.

The second point is that most people probably haven’t heard of Fritz Haber. He joins a long list of “nameless but hugely important” people in history. Yes, these are the scientists, bureaucrats, and administrators lost to history. But, most often, it’s women. In my Mini Philosophy poll, out of hundreds of responses, there was not one woman. Not a single woman. But all of the people listed above as the “greatest” had a mother. They had carers and a support network. They existed as part of a whole — they were the trophy-swinging, headline-grabbing celebrities, but as Newton (featured) famously said: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” “Giantesses” is probably more apt.

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

Next Week:

Next week, we’re exploring the philosophy of rest and leisure with Alex Soojung-Kim Pang. And so, I’m asking:

What does the perfect “rest day” look like for you?

Send me your thoughts via email or comment below.

MINI READING LIST

RESOURCES

This newsletter contains my reflection on the topic at hand. Here is a list of the material shared in this email, as well as extra content about the topic that I've shared on my other social platforms:

The companion article inspired by my conversation with Anton Howes

My short video exploring the fixation on big names in history, featured on Mini Philosophy’s Instagram page

The full, unedited audio interview with Anton Howes:

Jonny is the creator of the Mini Philosophy social network. He’s an internationally bestselling author of three books and the resident philosopher at Big Think. He's known all over the world for making philosophy accessible, relatable, and fun.

More Big Think content:

Big Think | Big Think Business | Starts with a Bang | Big Think Books

I'd have to agree that Newton was the most influential...It's hard to justify that Gutenberg isn't on the list but I'd like to throw curve at you. Yersinia Pestis, the plague bacterium. Of course it killed millions over several pandemic episodes but by drastically reducing the population gave rise to the elevation of the common man as a resource for labor. The Renaissance owes much to the chaotic impact of this contagion and the Enlightenment sprouted it's seeds in the rich soil of the newly minted worthiness of the somewhat empowered everyman

My perfect "rest day" is always a no make-up day where I get to wear jeans, a sweat shirt and hiking shoes and head out into nature. A day when I can walk up and down wooded hills, around ponds, along a lake shore or through a meadow. And I walk at a leisurely pace stopping to gaze at the smallest wonder of nature or looking high up to see an eagle soaring over its nest. It could be the white bones of a deer who didn't make it through winter, a snake making its way along the side of my walking path, the sweet orange blossom- like scent of early spring blooming Witch Hazel trees or the sound of moving water falling over rocks in a stream. It's all good and it leaves me renewed believing all is well with the world.